Optimizing GPU Programs from Java using Babylon and HAT

Key Takeaways

- The Heterogeneous Accelerator Toolkit (HAT) is a parallel programming framework that allows Java developers to offload Java code and dispatch the generated code on modern hardware accelerators, such as Graphics Processing Units (GPUs).

- HAT can be used to speed up massive parallel workloads such as Deep Learning, AI, big data analytics and physic simulations, just to name a few, by automatically offloading and running these workloads on specialized hardware.

- HAT provides programming abstractions to facilitate GPU programming from Java: some key abstractions are an ND-Range API, a compute-layer and a kernel layer which allow Java developers to write explicit parallel code that can be offloaded to GPUs. Besides HAT provides memory abstractions that facilitate the usage of custom data structures and efficiently map them to the different memory regions of the GPUs.

- This article provides an overview of the HAT programming model: using the matrix-multiplication as an example, we demonstrate how Java developers can tune GPU workloads from the Java side to achieve performance close to native cuBLAS, scaling from 7 GFLOP/s on CPUs to 14 TFLOP/s on an NVIDIA A10 GPU.

Outline

Introduction

The project Babylon is a new OpenJDK project with the goal of enhancing Java reflection, allowing to reflect code from Java methods and Java lambdas, and being able to query their symbolic representation, called code models. These code models can be used at runtime to modify the code, perform optimizations, and/or perform code transformations to other programming models. Furthermore, code reflection allows Java developers to interact with foreign programming models and foreign programming languages without using any 3rd party libraries.

One of the foreign programming environments we are exploring in the project Babylon is the GPU environment through the CUDA and OpenCL programming models, called HAT ( Heterogeneous Accelerator Toolkit). The goal for HAT is to be able to offload and run efficient parallel workloads on hardware accelerators.

Through this article, we want to tackle these two questions:

- Is it possible to write parallel programs for GPUs using Java constructs?;

- If so, can those Java programs be competitive to native solutions?.

Each of these questions presents its own set of challenges. The majority of the projects focus on the first challenge with projects such as Sumatra, Aparapi, Marawacc, RootBeer, JaBEE, IBM J9, and more recently TornadoVM. These projects have focused on abstracting GPU programmability and make it easier for Java developers. While they achieve reasonable high performance ( e.g., TornadoVM’s study) by leveraging specialized accelerators, they often do so at the cost of hindering access to advanced GPU optimizations. However, in the era of AI and high-demand computing, simply being faster than Java on CPUs might not be enough.

The second question goes a step further and rethink about how Java programmers could approach native performance on hardware accelerators while still maintaining reasonable high-level constructs. This is a very thin line between what to expose from low-level APIs and from what level of the native software stack. The HAT project tackles GPU programming from a perspective of a performance engineer wanting to efficiently interconnect the Java software stack with foreign GPU programming models. As we will see in this article, this allows programmers to perform fine-tuned optimizations for GPUs. We will look at the details, but in a nutshell, this is being possible because of recent innovations within the JDK development, such as Project Panama and its foreign function API, Project Babylon with its enhanced code reflection APIs and HAT.

In this article, we’ll take a hands-on approach to GPU programming from Java, using Babylon and HAT to implement and optimize the matrix multiplication application, one of the key algorithms widely used in AI and Large Language Models (LLMs) these days. Some implementations are inspired on the excellent blog from Simon Boehm, who applied a set of CUDA optimizations for the SGEMM algorithm to be able to run as close as cuBLAS (native GPU library for linear algebra) as possible.

We’ll step through each layer of optimization expressed in Java and HAT, analyze their performance using real-world profiling data, and compare our results to best-in-class libraries like NVIDIA’s cuBLAS.

Who is the article for? This article explores how Project Babylon and HAT can be leveraged to optimize code for GPU architectures. While we cover the fundamental GPU programming and execution models necessary for the HAT development, readers with prior experience in GPU programming will find these concepts familiar.

We specifically target Java developers interested in how the new code reflection enables GPU acceleration directly from the Java ecosystem, and how some Java applications can be accelerated on modern hardware. Furthermore, while the primary focus of HAT is GPUs, the optimization techniques discussed in this article can be applicable to other hardware accelerators and foreign language interfaces.

Introduction to HAT

As we have mentioned, HAT is a programming toolkit that enables Java developers to target heterogeneous computing systems from Java. To do so, HAT offers a set of programming abstractions on top of the lower-level foreign programming models for GPUs:

-

ND-Range API that defines GPU’s global thread configuration and block thread configurations. This is a similar concept to OpenCL, CUDA and SYCL in which programmers can define how thread blocks are structured. This makes HAT programs scalable and flexible when running on multiple hardware accelerators from different architectures and vendors.

-

A Kernel-Context Layer: this abstraction represents the code to be offloaded to the GPUs. These are Java methods that express the work to be done per thread (as in a GPU thread), similar to CUDA and OpenCL. To do so, HAT also exposes a KernelContext object, which gives access to Java developers to GPU’s global and local thread-ids, block partitions, and barriers.

-

Compute-Context Layer: this is a higher-level programming abstraction on top of the kernel context API to allow developers to compose a graph of compute kernels and their data dependencies. For example, if we want to launch multiple programs on a GPU, we can group all invocation under the same compute-context layer.

-

Interface Mapper for global and device memory: good memory handling is as important as good compute handling when it comes to achieving performance on GPUs from managed runtime systems. HAT exposes an API on top of the Panama FFM Memory Segments and an API for programming different device types from Java. With these APIs, developers can express their own data types and map them efficiently to different memory regions of the GPUs.

Let’s take a simple example to see all these concepts in practice. We are going to express vector multiplication for float arrays. Let’s start with the Java code:

public void vectorMul(float[] a, float[] b, float[] c) {

for (int i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

c[i] = a[i] * b[i];

}

}This is a straightforward code that iterates over the input arrays to perform the computation. Now, let’s do a minor modification, that hopefully, facilitates understanding when we will see the equivalent code in HAT. We could express the same vector computation by splitting into two methods between the loop structure and the loop body as follows:

public void compute(int i, float[] a, float[] b, float[] c) {

c[i] = a[i] * b[i];

}

public void vectorMul(float[] a, float[] b, float[] c) {

for (int i = 0; i < a.length; i++) {

compute(i, a, b, c);

}

}What we have done is to define a method that expresses the work to be done per iteration. And this is the idea behind expressing kernels in HAT. The following code snippet shows the kernel function (Java method that will be offloaded and accelerated on a GPU) expressed in HAT:

@Reflect

public static void vectorMul(@RO KernelContext kc,

@RO F32Array arrayA,

@RO F32Array arrayB,

@RW F32Array arrayC) {

int valueA = arrayA.array(kc.gix);

int valueB = arrayB.array(kc.gix);

arrayC.array(kc.gix, (valueA * valueB));

}First, we annotate the code with the @Reflect annotation from the code reflection API. This indicates the HAT compiler to offload this entire method to the GPU, from which it can obtain the code-model, perform a set of transformations (for example represent parallel constructs directly in the code-model), and generate the GPU code.

From the HAT kernel code above, we also see that there are different method parameter types:

KernelContext: each kernel method receives a kernel context object. This is a special object in HAT, as we introduced earlier, that provides the built-ins functions to access parallel GPU constructs (e.g., the global thread-id -kc.gix).F32Array: These objects correspond to HAT data types to representfloat[]in Java. The difference is that they are implemented on top of the Panama FFM API. Programmers can also provide their own data types by extending the HATBufferinterface. For example, the following code snippet defines an array ofshortvalues:

public interface MyArray extends Buffer {

int length();

short array(long idx);

void array(long idx, short i);

Schema<MyArray> schema = Schema.of(MyArray.class,

arr->arr.arrayLen("length").array("array"));

}Note also that parameters are tagged with the @RO (Read-Only), and @RW (Read-Write) Java annotations. This indicates the HAT runtime how to move data from the CPU to the GPU and vice versa, since memory between discrete GPUs and the CPU is not shared. However, this is quite likely going to change in future versions of HAT, becoming an optional tag.

From the kernel-context object, we can obtain the thread-id, and that’s the equivalent to our loop-index from the Java version. We access the different elements of the arrays by using the kc.gix (GPU’s global thread index), and store the result of the multiplication in the resulting array (array C).

But, how do we know how many iterations (threads) to run? Here we map the iteration with the thread-index. In GPU programming, it is a common practice to map the thread-id with the data-item to compute. Thus, ideally, we will launch as many threads as elements from the input arrays (e.g., a.length). Since we specify the threads to run at runtime, we need a way to protect us from getting a buffer overflow. The complete version of the kernel is defined as follows:

@Reflect

public static void vectorMulHat(@RO KernelContext kc,

@RO F32Array arrayA,

@RO F32Array arrayB,

@RW F32Array arrayC) {

if (kc.gix < arrayA.length()) {

int valueA = arrayA.array(kc.gix);

int valueB = arrayB.array(kc.gix);

arrayC.array(kc.gix, (valueA * valueB));

}

}Then, we only perform the vector multiplication only if the current thread-id is not higher than the maximum threads launched.

Note on Abstractions for Accessing Arrays in HAT: Array Views To access the data from a F32Array, or any array type that the HAT API exposes, we need to call the array method. This essentially is a getter method. However, HAT also provides high-level abstraction for array types that allows us to create views of arrays to facilitate GPU programming, particularly when we have to access multiple arrays within the kernel method.

For example, to access the data using the thread-id:

int valueA = arrayA.array(kc.gix);We can express it with a view as follows:

float[] arrA = arrayA.arrayView();

// Load

int valueA = arrA[kc.gix];

// Store:

arrA[kc.gix] = someValue;Java programmers can choose which representation to use, and since both approaches generate the exact low-level GPU code, programmers do not have to worry about these abstractions impacting performance. For the rest of the article, we use the usual notation get and set through the array method.

Compute Context and ND-Range So far we have seen two of the core API components: the compute-kernel API (the actual Java method to be offloaded and the kernel-context object), and the IFace memory buffers with the F32Array object type.

Next, we need a way to specify the total number of threads (or how many iterations) we want to process. This is done through and ND-Range object. We define the ND-Range in a compute-context method as follows:

@Reflect

public static void computeContext(@RO ComputeContext cc,

@RO F32Array arrayA,

@RO F32Array arrayB,

@RW F32Array arrayC) {

NDRange ndRange = NDRange.of(Global1D.of(arrayA.length()));

cc.dispatchKernel(ndRange,

kc -> vectorMulHAT(kc, arrayA, arrayB, arrayC));

}HAT defines ranges in 1D, 2D and 3D. We will dive in into these multidimensional ranges later when we optimize the matrix multiplication algorithm, but in a nutshell, they represent a way to organize and map threads to data. Usually, when we have 1D data structures, we define a 1D range. Similarly, when we have 2D data structures, we usually define a 2D range. As a programmer, you decide the range that best suits your application.

In HAT, you can also define a Local range. This corresponds to thread-partitioning (we can create smaller partition of threads from the global sizes, called blocks). If we don’t specify a block size, the HAT runtime will decide one for us. Thread-blocks are particular important when we want to share data across different threads, because, on GPUs, data can only be shared across threads within the same block. We will analyze this in more detail when we optimize the matrix-multiplication application. For example, if we want to specify a block size of 256 threads, we can do the following:

NDRange ndRange = NDRange.of(Global1D.of(arrayA.length()),

Local1D.of(256));If, for example, arrayA is of size 1024, we can create four groups of 256 threads.

Another important observation is that the computeContext is also annotated with @Reflect. This allows the HAT runtime and the HAT compiler to inspect all reachable kernels (methods to accelerate) and optimize the data flow across those kernels. Next, let’s take a look at how HAT compiles code and how it interacts with code reflection.

How Code Reflection is used in HAT?

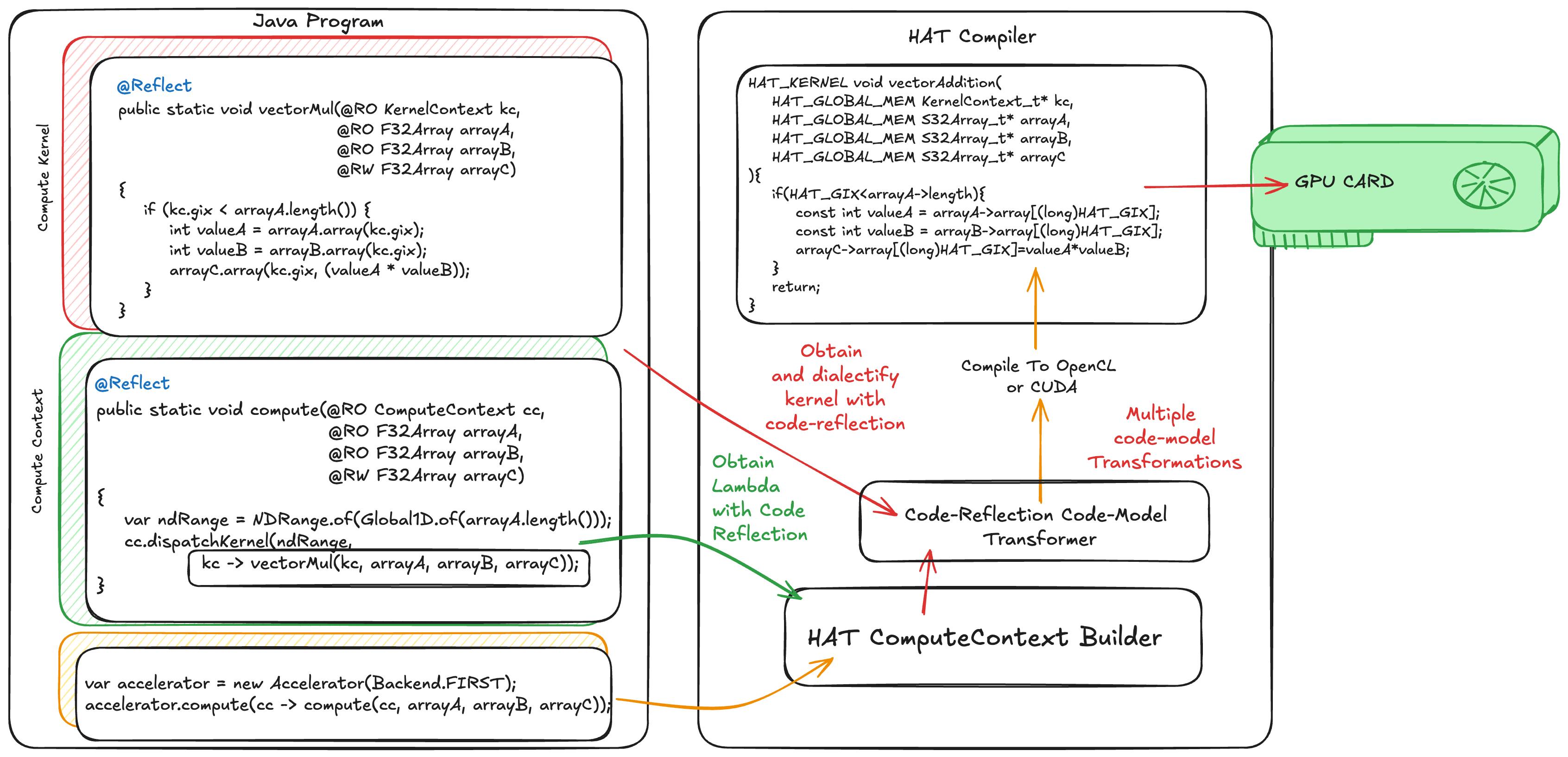

The following diagram shows an abstract representation of all components of the HAT software stack and how they interact with code reflection. The left-hand side of the diagram shows the Java program with the kernel method on the top, and the compute method with its ND-range definition. At the bottom-left, we have an invocation to an accelerator. We haven’t introduced this yet. This is just an object that bundles a hardware accelerator with an entry point in the compute layer. Between accelerator and the compute layers, programmers can compose complex applications with multiple kernels and multiple thread-configurations.

Furthermore, the accelerator and the compute-layers are used to build the whole compute-graph. This is the time in which HAT retrieves all reachable code models from the code reflection API that are annotated with @Reflect, builds its code model, and passes a set of transformation to translate the original code model into a GPU-friendly code model.

When all transformation are performed, HAT generates the corresponding low-level code. If we dispatch the application with the CUDA backend, HAT generates an equivalent CUDA program. Similarly, if we dispatch the application with the OpenCL backend, HAT generates an equivalent OpenCL program.

Then, HAT launches the application on the corresponding accelerator. Note that the data movement, compilation, and execution handler to be able to launch programs on GPUs are hidden from the developer.

Where can you run HAT?

At the time of writing this article, HAT offers two backends for GPUs: a CUDA backend to target NVIDIA GPUs, and an OpenCL backend to target any OpenCL-compatible device (including Apple M-chip, Intel CPUs, GPUs and FPGAs) and even ARM and RISC-V CPU system via OpenCL implementations such as OCK.

Furthermore, it offers a Java multithreaded backend, although, at the time of writing this article, some advanced constructs are not implemented just yet (e.g, 2D and 3D ranges and shared memory).

Optimizing Matrix Multiplication in Java with HAT

Let’s show HAT in action! We are going to program and run the Matrix-Multiplication example on an OCI instance, BM.GPU.A10, with an NVIDIA A10 GPU.

The source code of this example is fully available on GitHub, under the hat subdirectory of the project Babylon.

Before we dive in into the performance evaluation and HAT feature testing, let’s define the hardware and software stack we are using. The following table summarizes the hw/sw components:

| System Component | Version |

|---|---|

| OCI Instance | BM.GPU.A10 |

| CPU | Intel Xeon Platinum 8358 CPU @ 2.60GHz |

| System RAM | 236 GB |

| GPU | NVIDIA A10 |

| OS | Ubuntu 22.04.5 LTS |

| Linux Kernel | 6.8.0-1039-oracle |

| NVIDIA Driver | 580.105.08 |

| CUDA SDK | 13.0.88 |

| Java Version (Babylon) | 9b1ef462b0a |

| JDK Base Version | 26.ea.10-open (downloaded from sdkman) |

| Application | Matrix-Multiplication |

| Matrix Sizes | 1024x1024 (squared) |

| HAT Backend | CUDA |

A side note: The @Reflect annotation used to be called @CodeReflection. The evaluation was performed before this refactoring.

We use NVIDIA Nsight Compute (ncu) for profiling CUDA kernels on the GPU. This tool is a very useful kernel profiler used by CUDA developers that facilitates understanding of the computation and memory behavior of our kernels.

For measuring the elapsed time on the CPU, we run the Java multithreaded version multiple times (100 times) and take the average of all runs.

If you want to follow along and experiment with this example, the source code is fully available on GitHub under the HAT subdirectory (link).

Baselines

We will establish two baselines: one for the CPU and one for the GPU. We start with the CPU because it is likely more familiar for Java programmers. This baseline utilizes Java parallel streams to perform matrix-multiplication. Each CPU thread will perform a dot-product.

While we show the performance on the CPU, our primary goal is to benchmark multiple optimizations for GPUs expressed with HAT against the GPU baseline implementation. However, Java developers can get a high-level view of what GPU performance is when it compares to the CPU with Java.

Another important note is that, some techniques presented in this article to improve GPU kernel performance could be also applied for CPUs. However, many of these techniques are not directly available for Java developers, and the only solution would be to run native code via a JNI call.

Baseline for CPUs Running the Java baseline:

$ java -cp hat/job.jar hat.java run ffi-cuda matmul MT

...

Elapsed Time: 295976770 ns

Elapsed Time: 297536710 ns

Elapsed Time: 295931303 ns

Result is correct!The CPU version takes, on average, ~299ms (after warm-up). Note the OCI instance we are using is a paravirtualzed VM with 15 CPU cores.

Let’s calculate also the throughput for this benchmark, as the number of floating point operations per second expressed in GFLOP/s.

The following code snippet shows the floating point operations within the matrix multiplication kernel:

sum += matrixA.array(i * size + k) * matrixB.array(k * size + j);We have an addition and a multiplication per iteration, and we have size * size * size iterations: Since we are running with matrix sizes of 1024, the FLOPS are calculated as follows:

jshell> var flops = 2 * Math.pow(1024, 3)

flops ==> 2.147483648E9The total number of GFLOP/s can be computed as follows:

var gigaFlops = (flops * 1.0e-9f) / (ELAPSED_TIME / 1000.0f);Thus:

var gigaFlops = (flops * 1.0e-9f) / (299 / 1000.0f);

gigaFlops ==> 7.18...This Java method is able to run at 7.1 GFLOP/s. This will be our reference for CPU. Note that, in this synthetic benchmark, while we are running multiple times and reach the JITed code by Java JIT compiler, we don’t flush the caches and don’t set the CPU frequency. This is important to consider when compare against the GPU versions, in which we do control the cache behavior and set the GPU frequency. Thus, this will give the CPU version a slightly better advantage when comparing with the GPU versions.

Baseline for GPU Execution Let’s jump to our first GPU implementation. To be able to understand performance of the GPU kernel, we are going to measure just the GPU kernel elapsed time by using the NVIDIA Nsight Compute Profiler (ncu). Later, we will show the overall performance, including the cost of data transfers between the CPU and the GPU.

The ncu kernel profiling tool sets the GPU frequency and sets the memory system into a deterministic state. This will facilitate comparing GPU kernels obtain useful profiling information, not just the GPU kernel time.

Our first kernel is configured to run in 1D kernel.

@Reflect

public static void matrixMultiplyKernel1D(

@RO KernelContext kc, // GPU context

@RO F32Array matrixA, // first matrix

@RO F32Array matrixB, // second matrix

@RW F32Array matrixC, // result matrix

int size) {

if (kc.gix < size) {

for (int j = 0; j < size; j++) {

float acc = 0.0f;

for (int k = 0; k < size; k++) {

acc += (matrixA.array(kc.gix * size + k)

* matrixB.array(k * size + j));

}

matrixC.array(kc.gix * size + j, acc);

}

}

}Each GPU thread will run the two innermost loops to perform the matrix-matrix multiplication. In addition, we need to configure how many threads to run for this kernel:

var ndRange = NDRange.of(Global1D.of(1024), Local1D.of(16));

cc.dispatchKernel(ndRange,

kc->matrixMultiplyKernel1D(kc, matrixA, matrixB, matrixC, 1024)

);In this case, we are launching a 1D kernel with its global size set to 1024 threads. We can also specify the number of threads per block (called Local1D). This is an important value, and the best value will vary between GPUs. In our case we set it to 16 threads per block, and this will give us the highest performance with 1D configuration for this kernel on the A10 GPU. However, if you are running this example on another GPU, you may need to tune this number.

The GPU version takes 95ms (3x faster than the Java Parallel Stream version) (the GPU kernel elapsed time only, meaning that we exclude communications between the CPU and the GPU; more in this later). Thus, this means \(3x\) times faster than the previous version on the CPU, but, can we do better with HAT?

To profile the generated GPU kernel by HAT, we use the NVIDIA Nsight profiler analysis. The following table shows the summary of the ncu profiler:

matrixMultiplyKernel1D (64, 1, 1)x(16, 1, 1),

Context 1, Stream 13, Device 0, CC 8.6

Section: GPU Speed Of Light Throughput

----------------------- ----------- ------------

Metric Name Metric Unit Metric Value

----------------------- ----------- ------------

// Main Memory Frecuency

DRAM Frequency Ghz 6.24

// Frequency of the Stream Multiprocessor of the GPU

// (equivalent to a CPU core)

SM Frequency Mhz 885.00

// GPU cycles consumed

Elapsed Cycles cycle 84774133

// % of the peak memory throughput consumed

Memory Throughput % 18.71

// Kernel duration in ms

Duration ms 95.79

...

// % of the peak compute throughput consumed

Compute (SM) Throughput % 4.40

----------------------- ----------- ------------This table shows one of the main section of the ncu profiler report, the GPU Speed of Light (we only show a few entries). This section summarizes key metrics, such as the percentage of the peak memory and compute throughput achieved, the kernel duration, and L1 and L2 sustained throughput, etc.

For now, let’s look at the memory and compute throughput. From just these two values, we can see that the GPU utilization is extremely low, and in fact, the ncu profiler tool gives a hint about how to improve it.

This kernel grid is too small to fill the available resources on this device, resulting in only 0.1 full waves across all SMs.

In fact, this kernel can be represented as a 2D grid kernel, instead of 1D. We can also configure 2D as local thread-block size. Thus, we can increase the total number of threads, and we can increase the number of blocks. So, to do that, let’s jump to our first optimization in HAT.

First Optimization in HAT: 2D GPU Kernel

For GPU programmers (e.g., CUDA, OpenCL or SYCL programmers), this 2D representation is a straightforward representation of the program, and for GPU developers, this should be the initial way to express the GPU kernel. However, this might not be so trivial for Java developers, and for good reasons! Java developers do not have to think about GPU architectures and GPU execution models.

But this strengths one of the key messages of this article: code reflection, and Babylon, allows developers to enable specific optimizations when targeting foreign programming languages, such as CUDA.

The parallelization constructs of many the programming languages are in 1D (one dimensional), and this includes Java. However, some parallel programming models (e.g., CUDA and OpenCL) exposes multidimensional constructs to facilitate representation of parallel programs. Let’s say, if we have input matrices and each cell of the matrix can be computed completely in parallel, we usually represent a 2D kernel. The computation for each cell will be done by a unique thread. In reality, these multidimensional constructs are more a convenience for the programmer, and the actual runtime (e.g., OpenCL runtime and drivers) could implement multidimensionality on top of a 1D range space.

As programmers in HAT, we could also take advantage of this multidimensionality, and this is when the ND-Range API becomes handy. The following Java code snippet shows the HAT GPU kernel for expressing the matrix multiplication in 2D.

@Reflect

public static void matrixMultiplyKernel2D(@RO KernelContext kc,

@RO F32Array matrixA,

@RO F32Array matrixB,

@RW F32Array matrixC,

int size) {

// control for 1D range ( thread id 1D -> kc.gix )

if (kc.gix < kc.gsx) {

// conntrol for 2D range ( thread id 2D -> kc.giy )

if (kc.giy < kc.gsy) {

float acc = 0.0f;

for (int k = 0; k < size; k++) {

acc += (matrixA.array(kc.gix * size + k)

* matrixB.array(k * size + kc.giy));

}

matrixC.array(kc.gix * size + kc.giy, acc);

}

}

}Note that we removed one of the loops from the previous version:

for (int j = 0; j < size; j++)Instead, we can access the thread-id for the second dimension using the HAT construct kc.giy.

When we launch the kernel, we express a 2D NDRange as follows:

final int globalSize = 1024;

var ndRange = NDRange.of(Global2D.of(globalSize, globalSize),

Local2D.of(16, 16));

cc.dispatchKernel(ndRange,

kc -> matrixMultiplyKernel2D(kc,

matrixA,

matrixB,

matrixC,

globalSize));This new version launches \(1024x1024\) threads in blocks of \(16x16\). As a HAT programmer, we can play with different values of block sizes. And, if you are curious, I invite you to do so. You will experiment with another value for performance tuning on GPUs, deciding the right block size. I can tell, for our experiments on the A10 GPU, this value seems to be the most efficient one, but keep in mind that if you use a different GPU, this is one of the parameters to be tuned.

For convenience to Java developers, HAT also offers a simplified version to define ND-ranges.

var ndRange = NDRange.of2D(256, 256, 16, 16);The first two parameters corresponds to the dimensions of the global size, and the last two parameters correspond to local block size.

Let’s go back to our profiler. This new 2D version in HAT takes \(9.05ms\) (this is \(10x\) faster compared to the previous version!). Let’s take a look at the performance metrics.

matrixMultiplyKernel2D (64, 64, 1)x(16, 16, 1),

Context 1, Stream 13, Device 0, CC 8.6

Section: GPU Speed Of Light Throughput

----------------------- ----------- ------------

Metric Name Metric Unit Metric Value

----------------------- ----------- ------------

DRAM Frequency Ghz 6.24

SM Frequency Mhz 884.96

Elapsed Cycles cycle 8010119

Memory Throughput % 99.37

Duration ms 9.05

...

Compute (SM) Throughput % 23.31

----------------------- ----------- ------------Now the compute-throughput has increased to 23%, and the memory throughput to 99% of the peak value on this GPU. Usually, when there is a big difference between these two metrics and one of them is higher than 80%, the main suggestion is to shift one to the other. The NCU profiler also gives us another useful hint:

On average, only 4.2 of the 32 bytes transmitted per sector are utilized by each thread. This could possibly be caused by a stride between threads.

In another section of the ncu profiler, we obtain the following warning:

The memory access pattern for global loads from L1 might not be optimal. On average, only 4.2 of the 32 bytes transmitted per sector are utilized by each thread. This could possibly be caused by a stride between threads.

Thus, we can improve the memory access pattern. If you are familiar with the GPU programming model, you will quickly recognize this. One of the possible techniques to improve this kernel is to reorganize the memory access patterns to have global coalesced memory accesses.

Before we jump in into our next optimization, I want to highlight one of many optimizations the CUDA JIT compiler is doing for us: From the source section of the ncu profiler tool, we can also inspect the generated PTX (the CUDA intermediate representation) and SASS code (GPU program assembly code). For the previous 1D kernel as well as this new version, we see that a bunch of FMA (fused-multiply-add) instructions are generated.

FFMA R26, R33, R26, R18

FFMA R13, R13, R8, R26

FFMA R13, R10, R6, R13

FFMA R18, R16, R14, R13This is great, because, from the Java side, we did not specify any FMA operation, and the HAT JIT compiler does not currently have any compiler passes to optimize these math operations. But we see that the nvcc compiler and the driver JIT compiler are able to optimize these math instructions, very similar to what the Java JIT compilers (C1, C2 and GraalVM) do.

Now, let’s design our next optimization in HAT for the GPU.

Second Optimization in HAT: Global Coalesced Memory Accesses

If data to be accessed on the GPU are not contiguous, the GPU might need to fetch multiple cache lines to be able to load the right data, and if the data is also not present in the L2 cache, then the worst case is to continuously fetch the data from the GPU’s global.

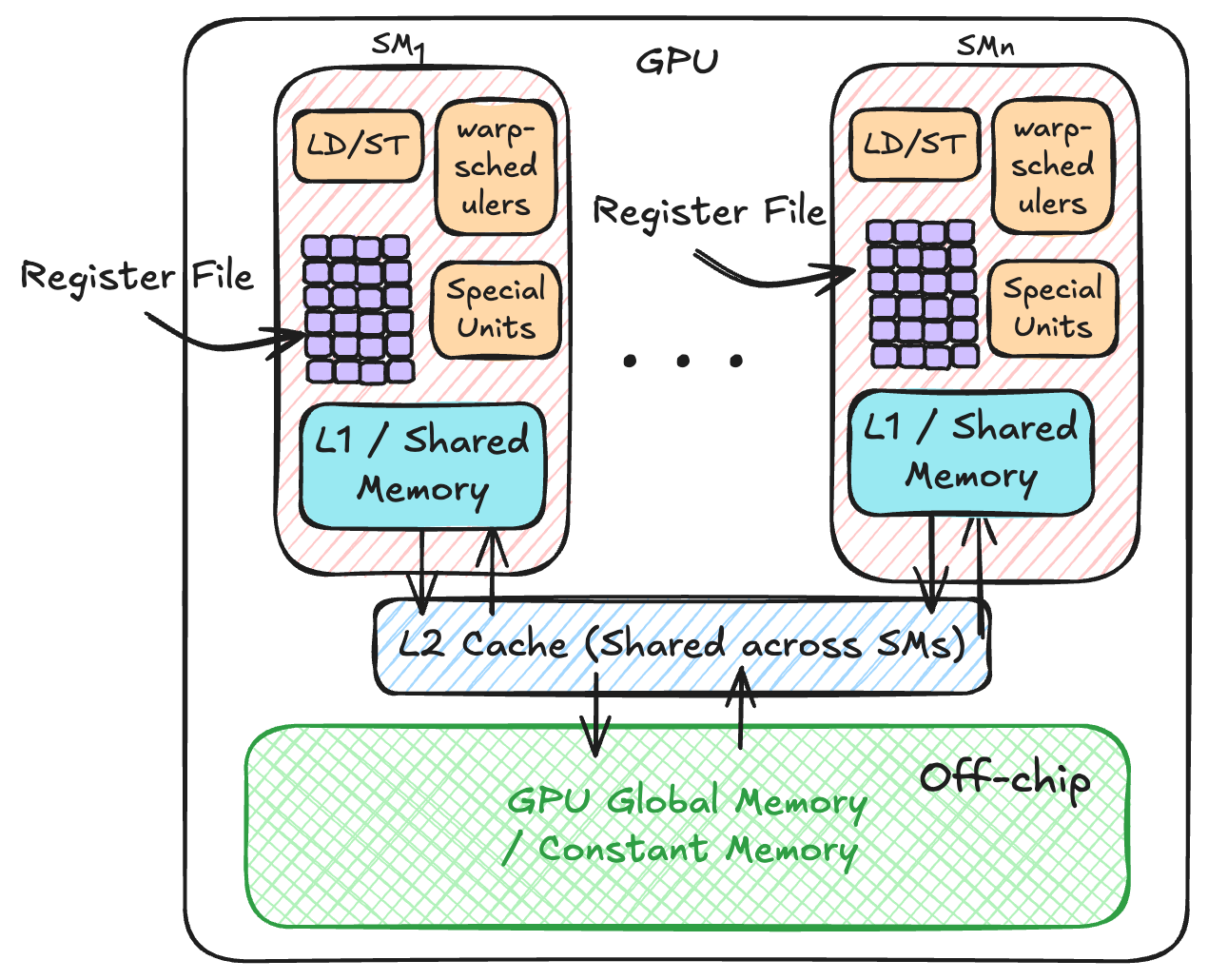

In a nutshell, GPU coalesced memory accesses occur when consecutive threads within a warp access consecutive memory locations, minimizing cache misses. A warp is a fundamental unit of execution on NVIDIA GPUs, representing a set of 32 threads that run in parallel on the same Streaming Multiprocessor (SM). An SM would be equivalent to a CPU core, and all GPU cores (CUDA cores in the case of NVIDIA GPUs) would be equivalent to functional units and vector units of CPU cores.

To know more about GPU memory coalescing and the GPU execution model, I refer to the following articles:

- Unlock GPU Performance: Global Memory Access in CUDA

- Optimize a CUDA Matmul Kernel for cuBLAS-like Performance

Analyzing our previous 2D kernel, we see that the memory accessing pattern is not optimal. This refers to this line of the Java code of our matrix-multiplication:

acc += (matrixA.array(kc.gix * size + k)

* matrixB.array(k * size + kc.giy));The performance of matrix operations is heavily dictated by the memory layout, and specifically whether elements are stored in row-major or column-major order. Programming languages like CUDA and OpenCL uses row-major memory layout to store n-dimensional arrays (e.g., a matrix) in memory. Thus, in HAT, we have also used the F32Array array-type to represent a 2D matrix into a flatten 1D array using row-major layout. To maximize GPU performance, we must ensure that memory access patterns are also coalesced, meaning the iteration over elements should align with the thread-id.

In our example we are using the global thread-id kc.gix (thread-id in the first dimension), and kc.giy (thread-id in the second dimension) to map and access the data elements of each matrix. However, following the NVIDIA documentation, the way we mapped thread-ids to access data results in not coalesced memory accesses. The reason is as follows:

“When using 2 or 3-dimensional thread blocks in a CUDA kernel, the threads are laid out linearly with the X index, or

threadIdx.x[(or global index)], moving the fastest.”

The threadIdx.x in CUDA is a built-in to access the local thread-id (thread-id within a block). In HAT, this is the equivalent of kc.lix. But our purpose here, it is also equivalent to our global thread-id (kc.gix).

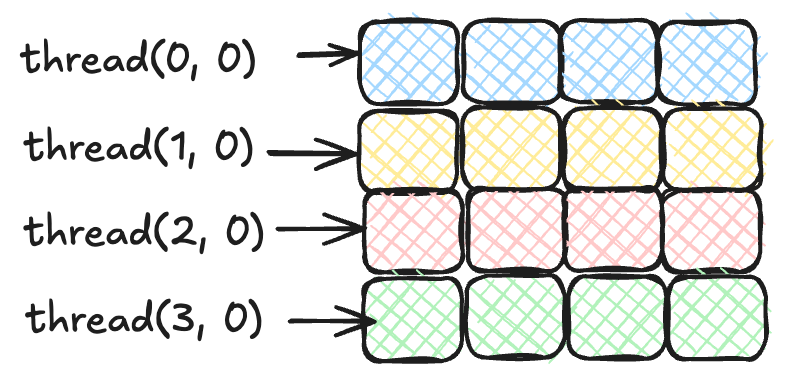

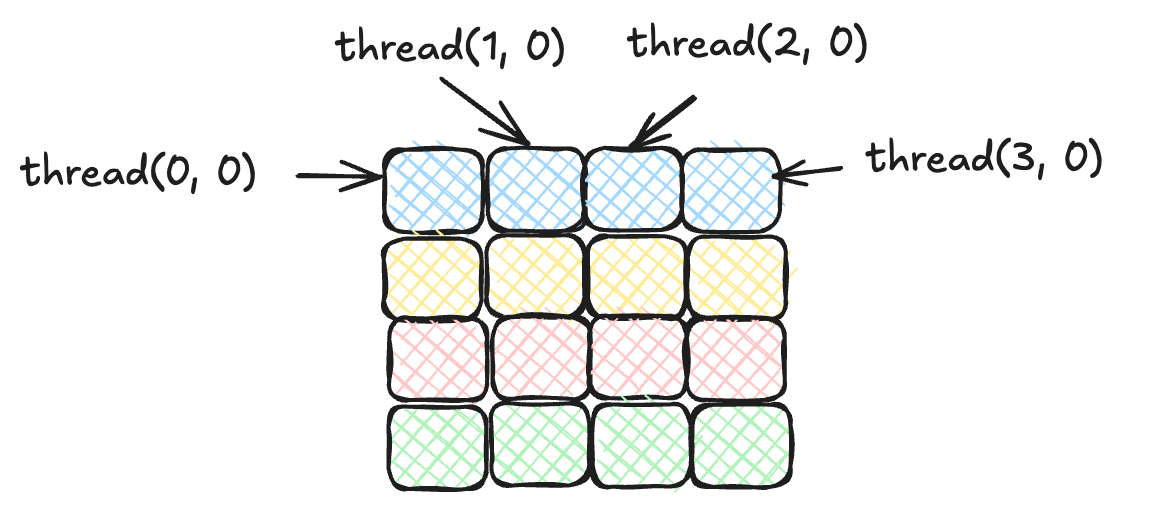

What does this mean in practice? For instance, if we have a \(4x4\) thread block, the way consecutive threads using a 2D configuration (kc.gix, kc.giy) is mapped are as follows:

(0, 0), (1, 0), (2, 0), (3, 0), (1, 0), (1, 1), (2, 1), ...If we map this to the HAT terminology, since the global-id in the first dimension moves faster in a 2D-range, this means that the kc.gix id moves faster. Thus, for this expression:

matrixA.array(kc.gix * size + k)The way memory is accessed is as follows:

Instead, what we want is the following:

In the case of HAT, to achieve optimal memory coalescing, the mapping must ensure that threads with consecutive kc.gix values within a warp access consecutive memory addresses. By assigning threads with the same kc.giy to a single row, the access pattern aligns with the matrix’s row-major layout.

To achieve this, we simply swap the indexes between kc.gix and kc.giy. Thus, instead of matrixA.array(kc.gix * size + k), we change the indexing to matrixA.array(kc.giy * size + k). We also do the same for the second matrix (matrixB). Note that matrixB is still not coalesced, but we will address this when we introduce shared memory.

The following code snippet shows the new version in HAT:

@Reflect

public static void matrixMultiplyKernel2DLI(@RO KernelContext kc,

@RO F32Array matrixA,

@RO F32Array matrixB,

@RW F32Array matrixC,

int size) {

if (kc.giy < kc.gsy) { // swapped gix -> giy

if (kc.gix < kc.gsx) { // swapped giy -> gix

float acc = 0.0f;

for (int k = 0; k < size; k++) {

acc += (matrixA.array(kc.giy * size + k)

* matrixB.array(k * size + kc.gix));

}

matrixC.array(kc.giy * size + kc.gix, acc);

}

}

}The kernel-dispatch (NDRange) remains the same. We can also keep the same block size (\(16x16\) threads).

When we profile this GPU kernel with ncu, we see that the kernel time takes 2.19 ms (\(4.1x\) times faster than the previous kernel!). But we are not done yet. What else can we do? Let’s take a look at the summary of the profiler:

matrixMultiplyKernel2DLI (64, 64, 1)x(16, 16, 1),

Context 1, Stream 13, Device 0, CC 8.6

Section: GPU Speed Of Light Throughput

----------------------- ----------- ------------

Metric Name Metric Unit Metric Value

----------------------- ----------- ------------

DRAM Frequency Ghz 6.24

SM Frequency Mhz 884.50

Elapsed Cycles cycle 1939911

Memory Throughput % 96.35

Duration ms 2.19

...

Compute (SM) Throughput % 96.35Now, the memory and compute throughput have increased to 96%.

If we look at the same memory section we looked before, we obtain this warning:

The memory access pattern for global loads from L1TEX might not be optimal. On average, only 14.4 of the 32 bytes transmitted per sector are utilized by each thread.

So we have improved from 6 bytes per sector to 14 bytes per sector out of 32 bytes per sector. Still, room for improvements here.

Since both compute and memory throughput are in equal percentage, the suggestion could be to reduce both by increasing the work per thread, and storing reusable data in shared memory of the GPU (scratchpad memory in which all threads running on the same Streaming multiprocessor of the GPU with the goal of having reusable data across coalescing threads). Let’s first tackle how we can express shared memory in HAT.

Fourth Optimization: Register Tiling

Let’s re-think what we did in the previous kernel. The previous implementation decomposes the input matrices into small matrices (tiles). The smaller matrices were stored in shared memory of the GPU, and compute the dot-product using the smaller matrices.

Similarly, we can build on the previous optimization by also copying the data from shared memory to private memory, and decomposing again arrays stored in shared memory to compute the dot-product in private memory using even smaller tiles. Besides, we are going to increase the work to be done per-thread, so each GPU thread will compute a sub-matrix (e.g., 4x4).

This version is heavily inspired by Simon Boehm’s on optimizing matrix multiplication, and it is equivalent to his version 5. If you are interested into the details of this optimization, I highly recommend reading his excellent blog.

The key differences compared to the previous kernel is that we have two types of DeviceType data structures: one for shared data structures to be allocated in shared memory, and another one for allocating into the private memory of the GPU. Besides, we have two different private regions:

- One for allocating a small 2D array in which we are going to perform the computation (dot-product).

- One dedicated to store partial results of each matrix from the shared memory space.

private interface SharedMemory extends DeviceType {

void array(long index, float value);

float array(long index);

DeviceSchema<SharedMemory> schema = DeviceSchema.of(

SharedMemory.class,

arr -> arr.withArray("array", 1024));

static SharedMemory createLocal() {return null;}

}

private interface PrivateArray extends DeviceType {

void array(long index, float value);

float array(long index);

DeviceSchema<PrivateArray> schema = DeviceSchema.of(

PrivateArray.class,

arr -> arr.withArray("array", 16));

static PrivateArray createPrivate() {return null;}

}

private interface FlatPrivate extends DeviceType {

void array(long index, float value);

float array(long index);

DeviceSchema<FlatPrivate> schema = DeviceSchema.of(

FlatPrivate.class,

arr -> arr.withArray("array", 4));

static FlatPrivate createPrivate() {return null;}

}Then, in the kernel:

SharedMemory tileA = SharedMemory.createLocal();

SharedMemory tileB = SharedMemory.createLocal();

...

// Declarations of the arrays in private memory

PrivateArray threadResults = PrivateArray.createPrivate();

FlatPrivate regM = FlatPrivate.createPrivate();

FlatPrivate regN = FlatPrivate.createPrivate();

// initialize values

for (int i = 0; i < (TN * TN); i++) {

threadResults.array(i, 0.0f);

}The first part of the loop-tile we copy data from the GPU’s global memory to the shared memory:

// Each thread loops over the tiles

for (int bkIdx = 0; bkIdx < size; bkIdx += BK) {

// A) Load data into shared memory for array A

for (int loadOffset = 0; loadOffset < BM; loadOffset += strideA) {

tileA.array((innerRowA + loadOffset) * BK + innerColA,

matrixA.array(((innerRowA + loadOffset) * size + innerColA) + aFrom));

}

// B) Load data matrixB into shared memory for array B

for (int loadOffset = 0; loadOffset < BK; loadOffset += strideB) {

tileB.array((innerRowB + loadOffset) * BN + innerColB,

matrixB.array(((innerRowB + loadOffset) * size + innerColB) + bFrom));

}

kc.barrier();Then, within the register-tile, we compute load from shared memory to private and pre-compute perform the computation:

for (int dotIdx = 0; dotIdx < BK; dotIdx++) {

// block into registers

for (int i = 0; i < TM; i++) {

regM.array(i, tileA.array((threadRow * TM + i) * BK + dotIdx));

}

for (int i = 0; i < TN; i++) {

regN.array(i, tileB.array(dotIdx * BN + threadCol * TN + i));

}

for (int resIdxM = 0; resIdxM < TM; resIdxM++) {

for (int resIdxN = 0; resIdxN < TN; resIdxN++) {

float val = regM.array(resIdxM) * regN.array(resIdxN);

float acc = threadResults.array(resIdxM * TN + resIdxN);

acc += val;

threadResults.array((resIdxM * TN + resIdxN), (acc));

}

}

}Lastly, we copy the final result from private memory to global memory:

for (int resIdxM = 0; resIdxM < TM; resIdxM++) {

for (int resIdxN = 0; resIdxN < TN; resIdxN++) {

float value = threadResults.array(resIdxM * TN + resIdxN);

matrixC.array((((threadRow * TM + resIdxM) * size

+ threadCol * TN + resIdxN) + (cFrom))

, value);

}

}This version is more complicated due to indexing the right block and the right tile.

Another key change is the number of global threads to be deployed. This changes because we are going to process more cells of the output matrix per thread.

var ndRange = NDRange.of(Global2D.of(256, 256), Local2D.of(16, 16));

cc.dispatchKernel(ndRange,

kc -> matrixMultiplyKernel2DRegisterTiling(kc,

matrixA,

matrixB,

matrixC,

globalSize));Since we process blocks of \(4x4\), each thread will process, in our version, 16 items. Thus, since our input size is 1024 elements, the new global size is reduced to \(256x256\) threads.

But have we got any performance improvement? Let’s take a look at the ncu profiler report:

matrixMultiplyKernel2DRegisterTiling (16, 16, 1)x(16, 16, 1),

Context 1, Stream 13, Device 0, CC 8.6

Section: GPU Speed Of Light Throughput

----------------------- ----------- ------------

Metric Name Metric Unit Metric Value

----------------------- ----------- ------------

DRAM Frequency Ghz 6.24

SM Frequency Mhz 881.14

Elapsed Cycles cycle 329296

Memory Throughput % 66.39

Duration us 373.47

...

Compute (SM) Throughput % 54.46

----------------------- ----------- ------------This kernel takes 373 microseconds! This is \(5.8x\) faster than our previous version, and we are now below 1 ms. And recall that our first kernel in HAT took \(~95ms\).

From the ncu report (source section of the profiler), we can also see that the memory throughput as well as the compute-throughput have decreased to 66% and 54% respectively. This is not necessarily a bad thing, as we just discussed, we increased the amount of work per-thread. But we will need to see other sections of the ncu report to check what we can do better.

Having a closer look at the source section of the profiler, it identifies the following warning in the SASS code:

Uncoalesced Global Accesses: 33% of this line's global accesses.From this line of the Java source code:

matrixA.array(((innerRowA + loadOffset) * size + innerColA) + aFrom);That generates the following SASS code (GPU’s final assembly code):

LDG.E R24, [R16.64+0x4] <<< WARNING IDENTIFIED HERE

MOV R19, UR7

IMAD.WIDE R12, R13, 0x4, R16What we can try to alleviate this by using vector types to load multiple elements at once accesses, using, for example, four floats per transaction.

Fifth: Adding Loads/Stores using Vector Types in HAT.

This new version is also heavily inspired by Simon’s blog. HAT offers a set of vector types, such as Float4 that can be used to load and store a set of float consecutive values in one transaction, as well as operate on float vectors.

In addition, the main types, such as F32Array, contain a method called float4View, which indicates the HAT compiler to perform a vload4 operation.

For example, in our matrix-multiply kernel:

Float4 loadA = matrixA.float4View((innerRowA * K + innerColA * 4) + aFrom);

tileA.array((innerColA * 4 + 0) * BM + innerRowA, loadA.x());

tileA.array((innerColA * 4 + 1) * BM + innerRowA, loadA.y());

tileA.array((innerColA * 4 + 2) * BM + innerRowA, loadA.z());

tileA.array((innerColA * 4 + 3) * BM + innerRowA, loadA.w());

Float4 loadB = matrixB.float4View((innerRowB * N + innerColB * 4) + bFrom);

tileB.array(innerRowB * (BN + extraCols) + innerColB * 4 + 0, loadB.x());

tileB.array(innerRowB * (BN + extraCols) + innerColB * 4 + 1, loadB.y());

tileB.array(innerRowB * (BN + extraCols) + innerColB * 4 + 2, loadB.z());

tileB.array(innerRowB * (BN + extraCols) + innerColB * 4 + 3, loadB.w());What we have done here is to create a view of the original F32Array that was not vectorized into a vector type element. The resulting value from the float4View operation is stored in private memory of the GPU. Then we need to copy elements from that vector type to shared memory. We can access individual members of that vector by selecting the lane ( x for the first lane, y for the second, and so on).

These are the main changes for this new version of the kernel. Now, let’s take a look at its performance.

matrixMultiplyKernel2DRegisterTilingVectorized (16, 16, 1)x(16, 16, 1),

Context 1, Stream 13, Device 0, CC 8.6

Section: GPU Speed Of Light Throughput

----------------------- ----------- ------------

Metric Name Metric Unit Metric Value

----------------------- ----------- ------------

DRAM Frequency Ghz 6.24

SM Frequency Mhz 881.35

Memory Throughput % 73.13

Duration us 373.73

...

Compute (SM) Throughput % 43.33

----------------------- ----------- ------------As we can see, the kernel time is almost identical to the previous version. However, compute throughput has decreased from 54% to 43%.

We are now entering a territory in which every tiny transformation matters. And one of the overlook optimizations we could apply is to perform auto-tuning (this is the testing of the different scheduling parameters such as block size, number of blocks, register tile sizes, etc.).

However, instead, we are going to explore one final optimization, that it is actually relevant to run Large Language Models (LLMs), and it is the ability to represent narrowed data types (e.g., half floating point number, aka FP16).

Sixth Optimization: Introducing FP16

I wouldn’t call this an optimization of the previous kernel, unless we know we can process our algorithms with less precision data types. However, this is an important feature these days with regard to LLMs that we are going to explore before we wrap up all optimizations.

So, how we can express narrow data types in HAT?

HAT exposes FP16 and array of FP16 using F16Array data structure. Similarly to the Float4 data type, the FP16 also contains a set of operations such as add, mul, etc.

Furthermore, the FP16 type can be used to compose custom types to combine it with DeviceTypes, and use it to store values in shared memory and private memory of the GPU.

In the case of the matrix-multiplication, we use both, the F16Array that is used to pass as a parameter to the HAT kernel, and custom device types. We can declare arrays of type F16 to be used as shared memory and private memory as follows:

private interface SharedMemoryHalf extends DeviceType {

F16 array(int index);

DeviceSchema<SharedMemoryHalf> schema = DeviceSchema.of(

SharedMemoryHalf.class,

arr -> arr.withArray("array", 1024)

.withDeps(F16.class, half -> half.withField("value")));

static SharedMemoryHalf createLocal() {return null;}

}

private interface PrivateArrayHalf extends DeviceType {

F16 array(int index);

DeviceSchema<PrivateArrayHalf> schema = DeviceSchema.of(

PrivateArrayHalf.class,

arr -> arr.withArray("array", 16)

.withDeps(F16.class, half -> half.withField("value")));

static PrivateArrayHalf createPrivate() {return null;}

}Then, within the kernel, we can create the arrays for each each region as follows:

// Declarations of the arrays in private memory

PrivateArrayHalf threadResults = PrivateArrayHalf.createPrivate();

FlatPrivateHalf regM = FlatPrivateHalf.createPrivate();

FlatPrivateHalf regN = FlatPrivateHalf.createPrivate();

// initialize values

for (int i = 0; i < (TN * TN); i++) {

F16 init = F16.of(0.0f);

threadResults.array(i).value(init.value());

}A few things to keep in mind:

FP16needs hardware support to be able to take advantage of the faster computation.- When using

FP16, we transfer half the amount of data compared toFP32(e.g., Javafloat). Thus, even if the hardware does not support it, but emulatesFP16, it is still possible to take advantage if we take into account data communications. This is something we have overlooked in this article, since we are focusing on GPU kernel optimizations.

If we run this new version on the A10 GPU, we see the following profiling metrics:

matrixMultiplyKernel2DRegisterTilingHalf (16, 16, 1)x(16, 16, 1),

Context 1, Stream 13, Device 0, CC 8.6

Section: GPU Speed Of Light Throughput

----------------------- ----------- ------------

Metric Name Metric Unit Metric Value

----------------------- ----------- ------------

DRAM Frequency Ghz 6.24

SM Frequency Mhz 881.43

Memory Throughput % 70.82

DRAM Throughput % 5.76

Duration us 281.50

...

Compute (SM) Throughput % 70.82

----------------------- ----------- ------------This kernel takes 281 microseconds, this is an 33% improvement over the previous version.

Comparing HAT vs Native CUDA cuBLAS

cuBLAS is a GPU-accelerated linear algebra library developed by NVIDIA for dispatching common Basic Linear Algebra Subprograms (BLAS) on NVIDIA GPUs.

These GPU kernels have been highly optimized by NVIDIA for their hardware. So now the question is, close far, or how close is HAT comparing to cuBLAS?

ampere_sgemm_128x64_nn (8, 16, 5)x(128, 1, 1),

Context 1, Stream 7, Device 0, CC 8.6

Section: GPU Speed Of Light Throughput

----------------------- ----------- ------------

Metric Name Metric Unit Metric Value

----------------------- ----------- ------------

DRAM Frequency Ghz 6.24

SM Frequency Mhz 879.61

Memory Throughput % 58.28

Duration us 241.98

...

Compute (SM) Throughput % 69.02

----------------------- ----------- ------------The GPU kernel takes 241 microseconds. This is \(1.54x\) times better than our faster kernel in FP32, and \(1.16x\) faster compared to our FP16 kernel. However, keep in mind that the cuBLAS version we are running does not use FP16, therefore, use this metrics just to put things into perspective, the fair-comparison should be against the FP32 kernel.

Another key observation is that the native cuBLAS kernel launches a kernel called ampere_sgemm_128x64_nn, as we see from the ncu profiler report, suggesting probably the block size of the selected kernel for the input data sizes. cuBLAS library contains a bunch of pre-compiled GPU kernels with different block sizes and different implementations. Then the library runtime selects the best fit for each GPU architecture and input sizes. Thus, there is still room for improvements when it comes to GPU thread scheduling in HAT.

Overall Performance Graphs

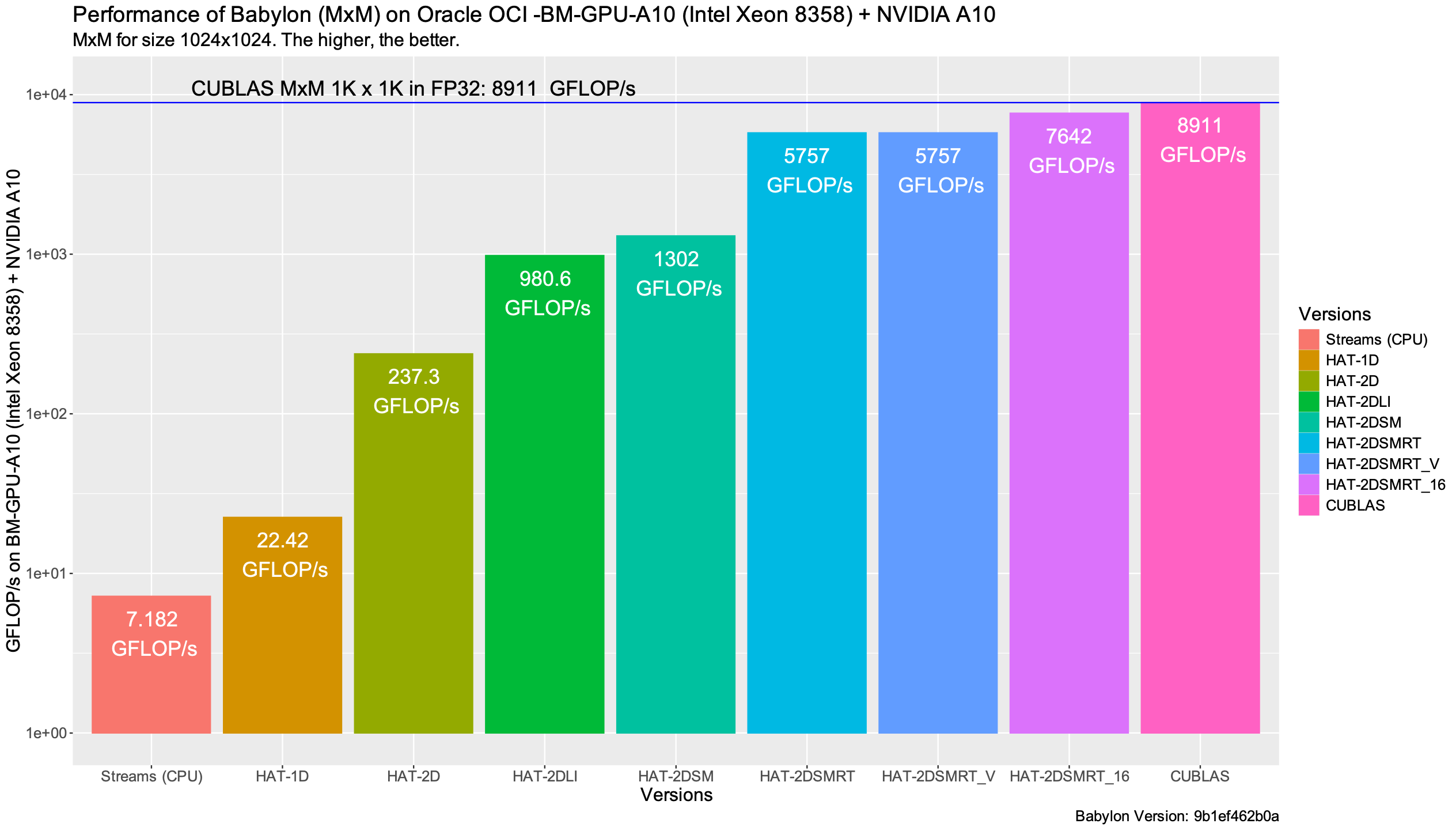

The following plot summarizes the performance obtained for each of the GPU kernels expressed in HAT compared to cuBLAS. Recall that cuBLAS does not use FP16.

The following performance graph shows the throughput (in number of floating point operations per seconds expressed in GFLOP/s) for each of the presented implementations. The higher, the better. As mentioned, we use the ncu profiler to obtain this data.

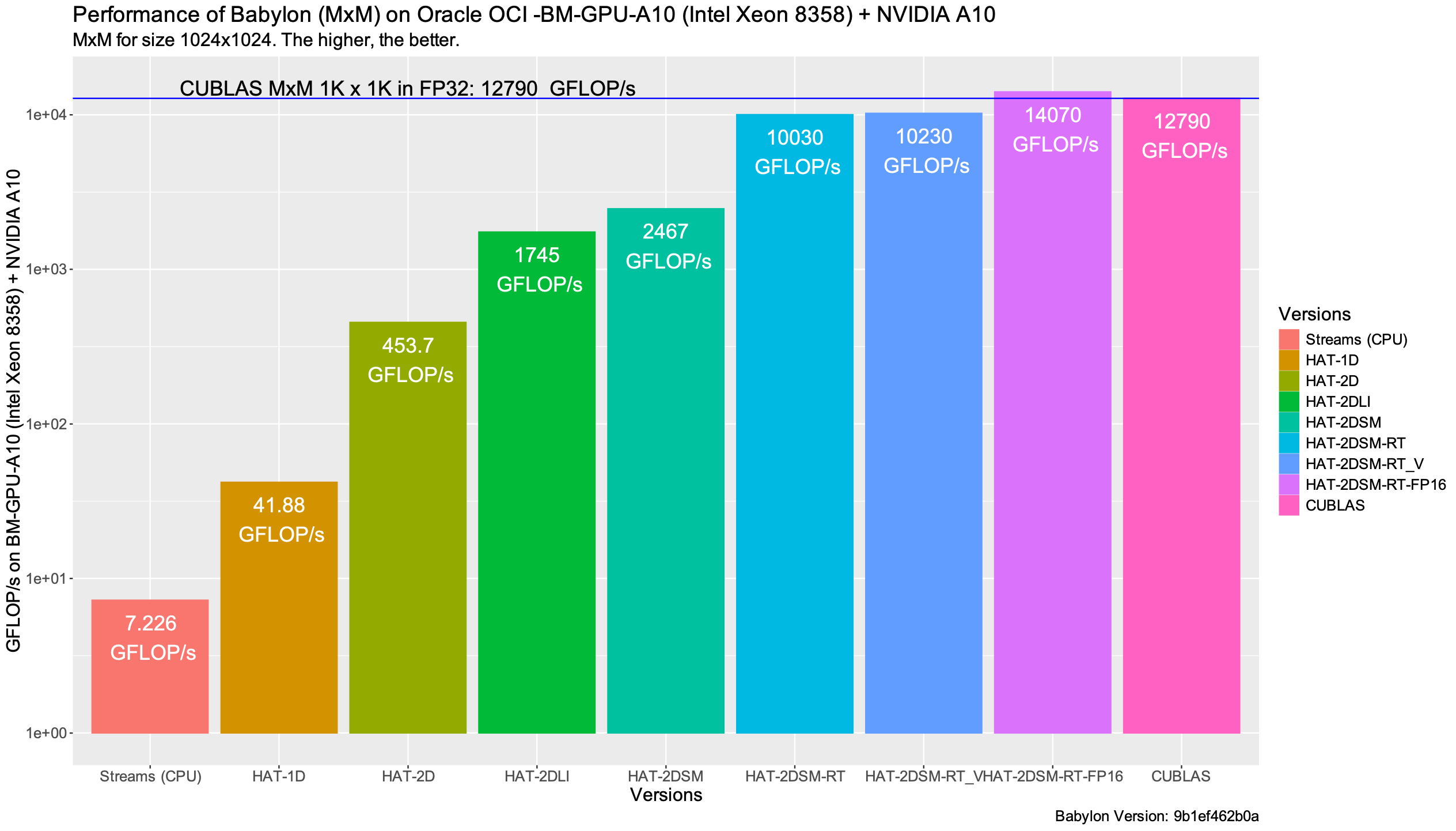

The ncu profiler, in order to deterministically compare different kernels, fixes the GPU frequency and controls the cache behavior. If we want just to measure the kernel time, we can use the CUDA Kernel events instead, as shown in the following performance graph. In this case, caches are not flushed, and the control of the GPU frequency is left to the GPU driver. From my perspective, this case represents a more real-world scenario.

We see higher performance compared to the previous graph: cuBLAS achieving 12.7 TFLOP/s and HAT achieving 10.2 TFLOP/s in FP32, and 14 TFLOP/s in FP16.

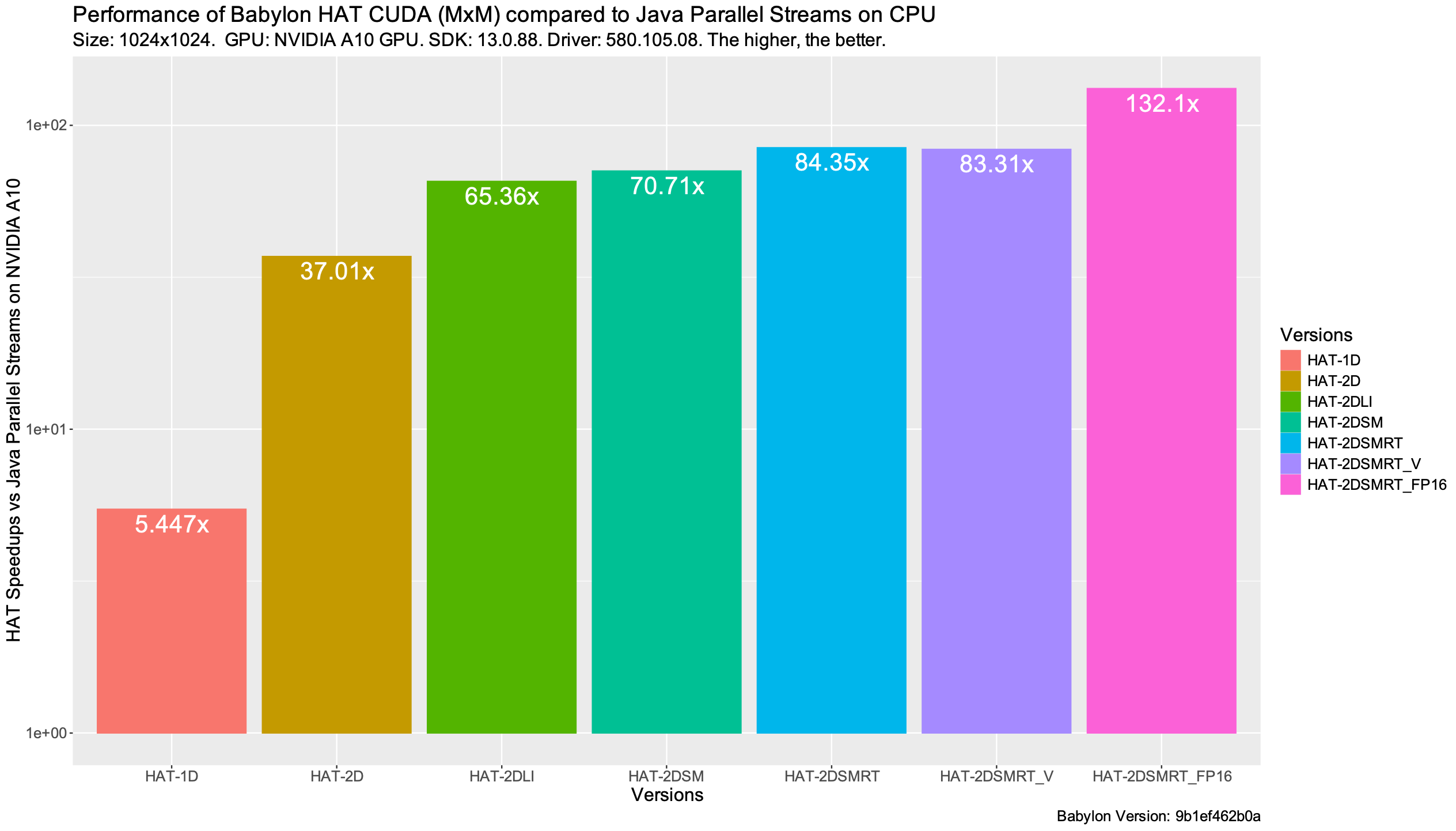

The last performance graph shows the end-to-end speedups (including kernel and data transfers between the GPU and the CPU) of each version HAT version of the matrix multiplication compared to the Java parallel streams on CPU. We see that HAT is able to achieve \(83x\) and \(132x\) over parallel streams when using an optimized version for FP32 and FP16 data types respectively.

Is it possible to improve it?

We have examined a set of common optimizations for matrix multiplication using HAT, but can we push these kernels further? The answer is yes.

Although we have demonstrated eight specific kernels, HAT is actively evolving. Future iterations aim to unlock some other advanced techniques, such as leveraging Tensor Core operations, or applying double buffering techniques.

Is it always possible performance close to native?

Achieving peak performance from high-level programming languages remains a formidable challenge, as it needs the precise orchestration of multiple architectural factors, including thread-block selection, block tiling strategies, and the deployment of hardware-specific intrinsics, just to name a few. Even with different GPU micro-architecture generations and different vendors, all previous parameters can be different.

In this article, we have focused on a single data point (data size) on a specific GPU to illustrate the mechanisms of code-reflection and HAT. These results demonstrate that with the appropriate language constructs, compiler support, and runtime systems, it is possible to bridge the performance gap between high-level abstractions and native parallel code. While performance portability and automated tuning remain open research questions, one of the most common techniques to achieve this is via auto-tuning, which could be included in future extensions of HAT.

Conclusions

In this article we have explored how the project Babylon with its enhanced code reflection APIs along with HAT, a parallel programming framework for offloading Java programs onto modern such as GPUs can unlock GPU acceleration and achieve performance close to native CUDA implementations.

By progressively optimizing the matrix-multiplication example from Java using HAT built-ins and HAT parallel constructs, we have shown how to apply advanced GPU optimizations such as 2D Local Ranges, loop tiling, shared memory, register tiling, vectorization and transformations to narrowed types such as FP16 in order to increase performance from single-digit GFLOP/s to over 12 TFLOP/s on GPUs.

Furthermore, along the explanation for each optimization, this article explained some key components of the HAT programming model and how those components relate to the GPU architecture and hardware accelerators. Since HAT is in active development, parallel constructs and APIs might evolve to higher level-abstractions, with the goal of facilitating GPU and heterogeneous programming for Java developers.

The innovations in Babylon and HAT illustrate how modern Java is evolving to address heterogeneous computing, bridging the gap between productivity and performance for foreign programming languages.

For those interested in further exploration, I recommend the following list of resources.